Papyri

6. Where can I find the papyri listed on my seminar handout? Where are they translated?

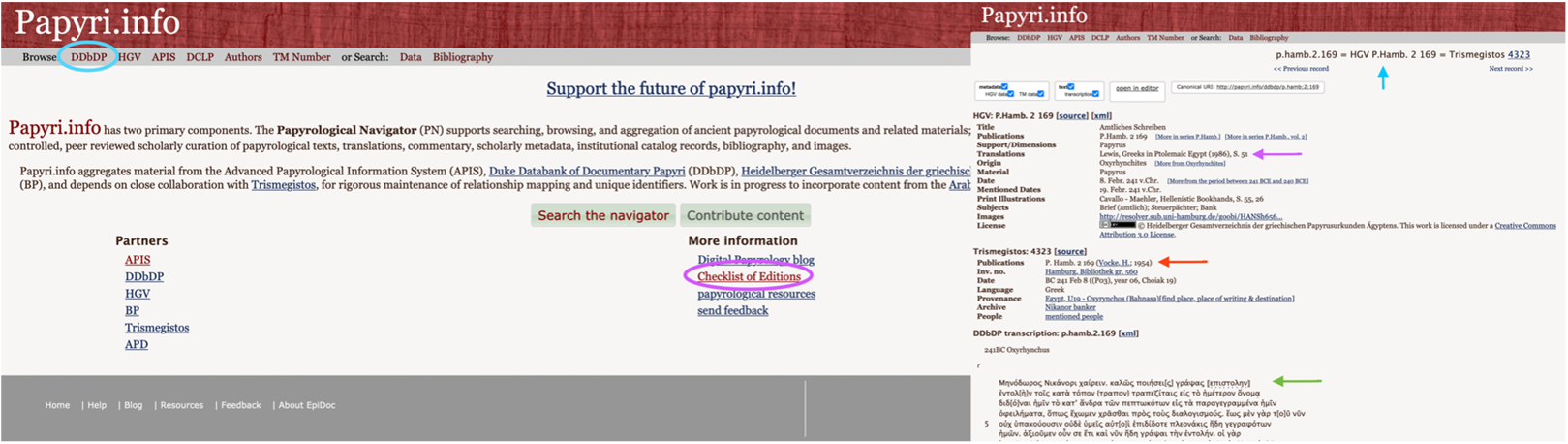

Left: Under DDbDP (light blue circle at top left) there is an alphabetical list of a substantial portion of the papyri in the collection. By clicking “Checklist of Editions” (purple circle in the centre) one obtains an overview of the abbreviations and editions (cf. question 5).

Right: The light blue arrow at the top indicates alternative edition designations. This means that the same papyrus has been edited and published elsewhere under a different title (on how to deal with this, cf. question 8). The purple arrow points to works which include a translation – in this case LEWIS NAPHTALI, Greeks in Ptolemaic Egypt, Oakville 2001, p. 51 (available in the Chair’s library). The red arrow indicates a publication of the same papyrus on Trismegistos, whereby via “source” (linked just above in the same line) one goes directly to the parallel text. The green arrow finally marks the start of the transcription of the respective papyrus in the original language.

Each seminar participant receives a handout from the Chair with helpful source- and literature references. Depending on the topic, these may also include references to relevant papyri. We recommend the following procedure, in case one also wishes to find a translation of the papyrus (usually Ancient Greek):

- Search for the papyrus on papyri.info.

- Look up the given edition (or editions: light blue arrow at the top) either online or in a library via Swisscovery, and check whether it includes a translation; only certain editions reliably include translations (for example the Oxyrhynchus series).

- If the edition does not include a translation: check whether papyri.info itself indicates a translation (at the end of the page).

- If no translation is found in this way: contact the Chair (lst.alonso@ius.uzh.ch) early so that a translation can be prepared.

Detailed examples of how to locate papyri and their translations are given further below.

It is often sufficient to type the given abbreviation of a papyrus into Google Search, possibly adjusting the spacing (for example, P. Heid instead of P.Heid.) and replacing Roman numerals with Arabic numerals.

Papyri.info contains, in addition to translation references, valuable metadata concerning each papyrus, which are relevant for citation (cf. question 9) and for placing the papyrus in its proper context.

Sometimes secondary literature on the topic also includes a translation, often in an unexpected setting. For this reason, consulting the seminar apparatus or visiting the Chair’s library is sufficient in many cases to access translated papyri.

Tip: It can be worthwhile to compare different translations of the same papyrus in order to obtain the most precise translation possible. If they differ only in phrasing, this is normally unproblematic. However, if the found translations diverge significantly in key points, one should contact the Chair in order to clarify the specific case.

7. Which fundamental works of Juristic Papyrology are suitable as introductions?

As the field of Juristic Papyrology is entirely new to most students and interested readers and can quickly appear overwhelming, the reading of certain fundamental works is recommended. Helpful and important introductory books and texts, which also contain further bibliographical references, include:

- ALONSO JOSÉ L., Juristic Papyrology and Roman Law in P. DU PLESSIS/C. ANDO/K. TUORI, The Oxford Handbook of Roman Law and Society, Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 56–69 (useful for initial orientation).

- BAGNALL ROGER S. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology, New York 2009.

- KEENAN JAMES G./MANNING J. G./YIFTACH-FIRANKO URI (eds.), Law and Legal Practice in Egypt from Alexander to the Arab Conquest, Cambridge 2014.

- MÉLÈZE-MODRZEJEWSKI JOSEPH, Le droit grec après Alexandre, Paris 2012.

- RUPPRECHT HANS-ALBERT, Kleine Einführung in die Papyruskunde, Darmstadt 1994.

- SCHUBART WILHELM, Einführung in die Papyruskunde, Berlin 1918 (available online ).

- SEIDL ERWIN, Rechtsgeschichte Ägyptens als römischer Provinz, Sankt Augustin 1973.

- WOLFF HANS J., Das Recht der griechischen Papyri Ägyptens in der Zeit der Ptolemäer und des Prinzipats, vol. I: Bedingungen und Triebkräfte der Rechtsentwicklung, Munich 2002.

These and other texts can regularly be found in the seminar apparatus under “General + Specific Literature” or “Juristic Papyrology” (cf. question 3).

8. What is an edition? What kinds of papyrus editions exist?

Reading papyri is often demanding: the script is usually cursive, without spaces between words. There is not actually any punctuation. Moreover, each scribe had their own handwriting, just as we do today. In addition, the vast majority of papyri survived only in fragments, which means parts of the original texts are lost. Numerous damages to the papyrus can further complicate comprehension. For these reasons, specialists develop editions in which the Greek text is reproduced as reliably as possible according to modern conventions (i.e. with spaces, punctuation, accents, etc.). More complex passages are represented using the Leiden Conventions, for example in cases of uncertain readings. A concise overview of the main symbols can be found on Wikipedia. These established texts form the foundation of papyrological research.

Papyrus editions are published in different forms:

- A considerable number of papyri are published in the major series, including the Oxyrhynchus (P.Oxy.), Michigan (P.Mich.) and Heidelberg (P.Heid.) collections, as well as the Berliner Urkunden (BGU) and the Vienna Papyri (CPR). Depending on the series, alongside the (Greek) text, there may also be a short introduction and commentary, and sometimes a translation into a modern language. Through their abbreviation (often with P.) and publication number, the individual papyri can be uniquely identified.

- Papyri published in scattered places (i.e. not in one of the established series) can be found in the Sammelbuch (SB). This contains neither translation nor commentary and is mainly to be used when no other edition of the papyrus can be found. However, under the heading metadata one can find references to previous publications. These details should usually also be visible on papyri.info.

- Papyrus editions can also be grouped according to content criteria (genre, origin, relation to a certain topic) in a corpus (plural: corpora). This form of publication has the advantage that the entire volume is dedicated to a single theme, and the individual papyri are thus clearly explained and contextualised. Related are papyrological florilegia and chrestomathies, in which papyri collected according to thematic criteria are likewise published.

If multiple editions of the same papyrus exist, the following points should help in selecting a suitable edition:

- Normally, the edition listed first on papyri.info (provided it is the most recent edition) should be considered authoritative.

- New editions are generally to be preferred, as they correct errors and incorporate the latest scholarly perspectives. For older editions, it may be advisable to consult the relevant Berichtigungsliste.

- In any case, at the first citation all editions of the same papyrus should be listed (cf. question 9).

9. How should I cite papyri?

At the beginning of a work, a bibliography and a separate list of sources should be compiled (cf. the stylesheet (PDF, 322 KB)). However, a dedicated papyrus list with all used papyri is generally not necessary and may only be appropriate for detailed Master’s theses and is not compulsory.

In the main text, each papyrus, like any other source, should be cited in a footnote, where as precise information as possible is expected: the origin and date of the papyrus (information can be obtained from papyri.info) should be included, as well as a clear indication of which edition was used and which translation underlies the work, if the papyrus was not translated independently. On first mention, all editions of the same papyrus should be listed. For subsequent mentions, it is sufficient to cite the first edition only.

In the list of abbreviations of the work, edition abbreviations should never be included unless a new abbreviation was created, which is rare.

For general guidance on citation practices, cf. documents.

Example: In the work, P.Abinn 9 was used. Searching for this papyrus on papyri.info (cf. question 6 for the exact procedure) shows under “Publications” all other editions of the same papyrus, the place of discovery under “Origin” and the time of creation under “Date”. Therefore, at the first mention in a footnote, the following should be indicated: P.Abinn 9 = P.Lond. II 231 = W.Chr. 322 = Sel. Pap. II 428 (approx. 346 CE, Alexandria). In all subsequent footnotes referring to this papyrus, it is sufficient to cite the first edition, including the date and place of discovery, i.e. P.Abinn. 9 (approx. 346 CE, Alexandria). Only if the papyrus in question is mentioned again in close proximity to the first reference, the date and place of discovery do not need to be repeated in the follow-up reference, i.e. P.Abinn. 9.

For further study

The following works are recommended as possible auxiliary means for working with papyri:

- KIESSLING EMIL, Wörterbuch der griechischen Papyrusurkunden, Amsterdam 1971.

- MCNAMEE KATHLEEN, Abbreviations in Greek Literary Papyri and Ostraca, Chico 1981 (available online; knowledge of Greek required).

- PREISIGKE FRIEDRICH/KIESSLING EMIL, Wörterbuch der griechischen Papyrusurkunden, Wiesbaden 1993 (key reference work documenting language use in papyri).

- TURNER ERIC G., Greek Papyri, Princeton 1968 (Chapter 5: notes on how a papyrus text is edited).

- Wörterlisten (useful when searching for specific names, expressions or persons).

Additional Useful Websites:

- The website Trismegistos, already mentioned in question 6, can also be employed for the search of papyri, allowing filtering by number, place of discovery or date. Scrolling down the entry for the desired item, one can, depending on availability, access the papyrus in its original text. A particular advantage of the texts available here is that hovering the cursor over a word in the original text displays a translation along with further explanatory notes. This feature is especially useful for investigating specific terms in a papyrus, although familiarity with Greek script is beneficial. A complete translation, however, is not provided.

- Occasionally, Google Scholar provides links to translations of selected papyri.

- The Advanced Papyrological Information System (APIS) contains images of the original fragments, detailed information (accessible by clicking on the image of a fragment) and, in many cases, English translations.

- For papyri from Spain specifically, the website DVCTVS is recommended. While it does not provide translations, it offers information on papyrological finds in Spain and a catalogue of images of the corresponding artefacts.

- For papyri from the Oxyrhynchus series, Oxyrhynchus Online is particularly useful, providing images of the original papyri. To locate a papyrus, only the Arabic numeral at the end of the siglum (P.Oxy.LXVI ____) needs to be entered.

- If a papyrus cannot be located directly, it may be worthwhile to consult specialised journals. For example, via the UZH VPN, one can access the Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik online, which contains valuable articles and editions. Online access is also available to The Journal of Juristic Papyrology.

Examples of Locating Translations of Papyri (cf. question 6):

Example 1: The seminar handout recommends a source with the siglum P. Freib. III 29. One begins by consulting the seminar apparatus and searching in the folder “Papyruseditionen” for the document P.Freib. 3 (note spacing and the use of Arabic rather than Roman numerals). By double-clicking, the volume opens, and scrolling to Papyrus 29, whose description in this case begins on p. 15, provides the text. On p. 22, the papyrus is printed in Greek in full. The advantage here is that a translation and commentary are usually appended.

In the Chair’s digital library provided on the seminar page (Excel file under “Files”), one can either search for the siglum directly (i.e., without the Arabic number; in this case P. Freib. III) or by author name (Mac: Command+F/Windows: Ctrl+F). Our volume is listed under the library siglum La1 P. Freib. III and can be consulted physically at the Chair’s library. The physical copy offers not only the text but also an extensive introduction and contextualisation, which are central to research.

Example 2: The handout cites SB XII 10967. On papyri.info, under the DDbDP menu, one can find an overview listing the abbreviation SB (for Sammelbuch). A further click reveals all available volumes, including the sought volume 12 (here in Arabic numerals). Navigating through the table now displayed leads to number 10967. Here, an English translation is appended alongside the transcription when one scrolls down.

Example 3: The handout lists P. Stras. I 22. Following the procedure outlined above on papyri.info yields the transcription but not a translation. Returning to the homepage and selecting “Checklist of Editions”, one can search for the full title corresponding to the abbreviation P. Stras., in this case “Griechische Papyrus der Kaiserlichen Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek zu Strassburg” (sic!) by FRIEDRICH PREISIGKE. The entry indicates that the work (volume I) is available online, where one finds both translation and extensive commentary.

If one prefers to consult the physical copy or no digital version is accessible, entering the title or at least key terms (if errors have crept into the full title, as in this case) in the Excel file of the Chair’s library yields the siglum La1 P. Stras. I. In many cases, the abbreviation alone already points to the correct entry.

In Swisscovery, the full title (or again relevant keywords) should be entered, filtered by author (here PREISIGKE). In this case the third result is optimal, as the first two are unavailable locally (requiring interlibrary loan, cf. question 14) and subsequent entries are merely articles or reviews. The physical copy can then be borrowed to access the translation.

Example 4: Research has led to the sixth volume of the Sammelbuch griechischer Urkunden aus Ägypten by EMIL KIESSLING, specifically document 9174 (the abbreviation therefore being SB VI 9174). In fact, this papyrus is not available on papyri.info. On Trismegistos, however, searching for SB 6 9174 identifies the papyrus and provides publication information. The first listed reference is “The Archive of Aurelius Isidorus”, with the number 94 corresponding to the papyrus in that compilation. Although this work is not found on Swisscovery, it is available in the Chair’s library under La1 P. Cair. Isid. The physical volume contains an English translation of the papyrus at the specified location (p. 340).